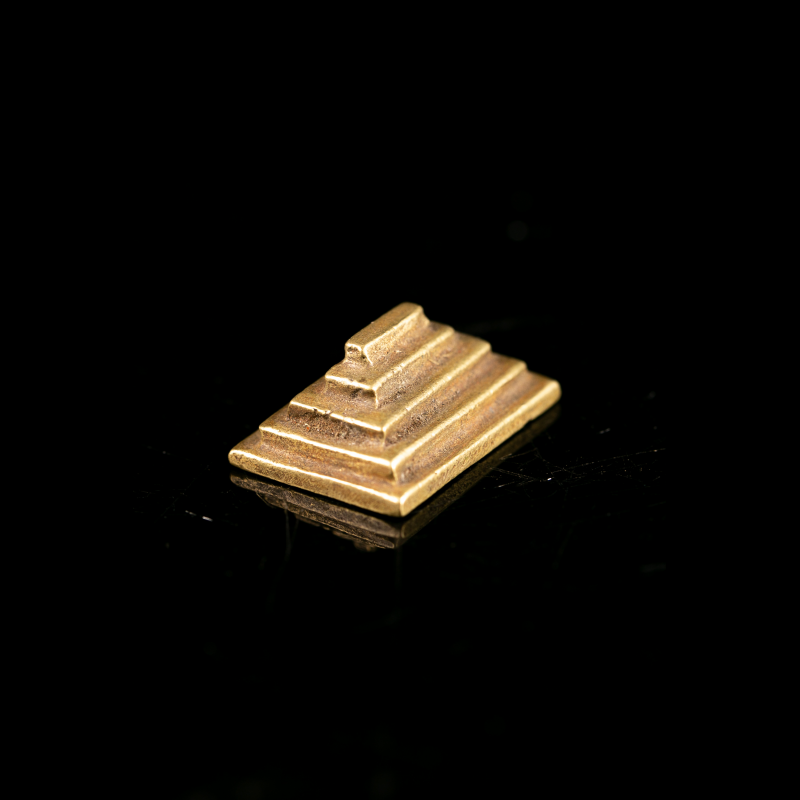

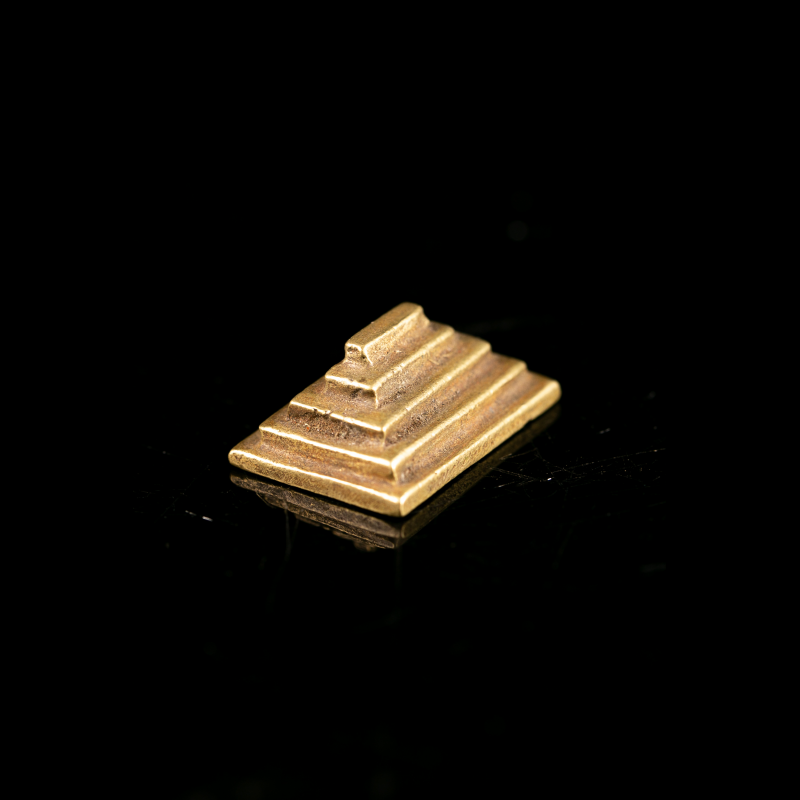

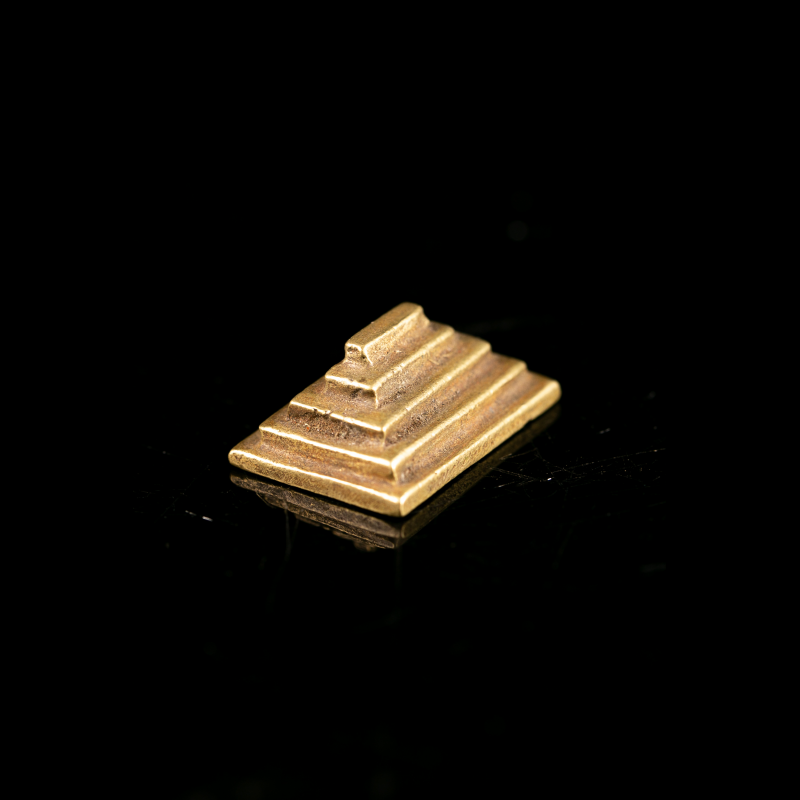

Akan gold weights, called mram or ahindra-yobwe in the Twi language, renowned in West African art, are much more than simple measuring instruments: they constitute a unique cultural and symbolic heritage in West Africa.

These small brass or bronze figurines, used from the 15th to the early 20th century, served to weigh gold dust, a major form of currency in the Akan kingdoms (Ashanti, Baoulé, Fanti, etc.), located primarily in Ghana and Ivory Coast. Their precision, often less than 2.5 ounces, testifies to remarkable craftsmanship, calibrated using the seeds of Abrus precatorius.

What makes these objects exceptional is their dual function: practical and symbolic. Each weight represents an element of daily life, nature, or Akan mythology – animals, plants, tools, scenes of social life, or Adinkra symbols. They thus form a veritable “miniature museum,” illustrating the values, proverbs, and founding narratives of the society. For example, a crocodile-shaped weight might evoke patience, while a seated human figure recalls the importance of wisdom and collective deliberation.

The Akan are particularly famous for these objects because their economic system was based on gold, an abundant resource in the region. The weights, kept in leather or fabric cases called dja, were much more than mere tools of commerce: they were status markers, prestige objects, and even educational materials, transmitting the philosophy and history of the people. Their use was overseen by specialists, often connected to the royal court, emphasizing their sacred and political dimension.

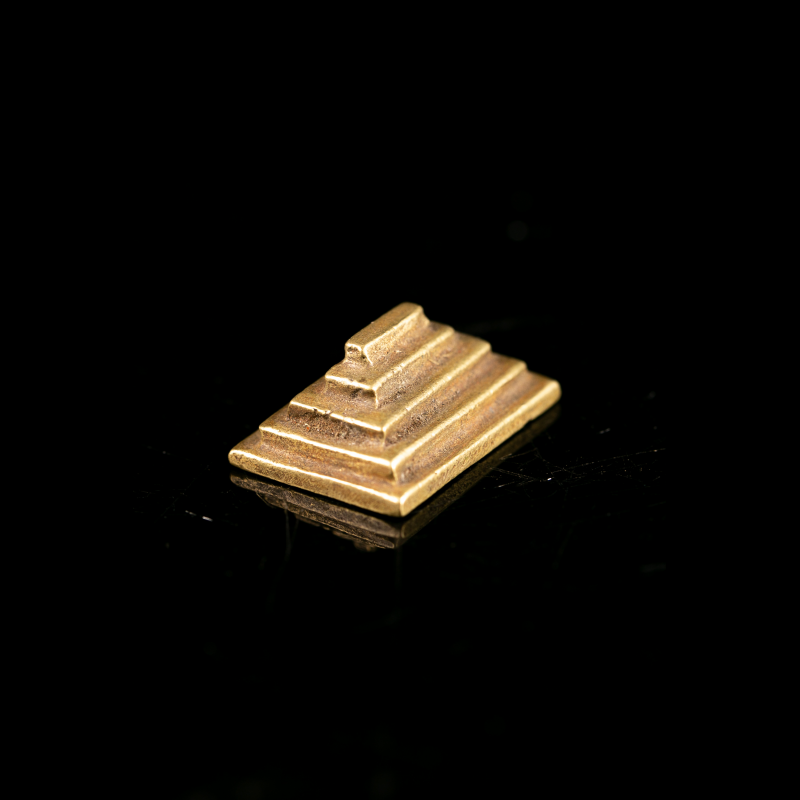

Akan gold weights, called mram or ahindra-yobwe in the Twi language, renowned in West African art, are much more than simple measuring instruments: they constitute a unique cultural and symbolic heritage in West Africa.

These small brass or bronze figurines, used from the 15th to the early 20th century, served to weigh gold dust, a major form of currency in the Akan kingdoms (Ashanti, Baoulé, Fanti, etc.), located primarily in Ghana and Ivory Coast. Their precision, often less than 2.5 ounces, testifies to remarkable craftsmanship, calibrated using the seeds of Abrus precatorius.

What makes these objects exceptional is their dual function: practical and symbolic. Each weight represents an element of daily life, nature, or Akan mythology – animals, plants, tools, scenes of social life, or Adinkra symbols. They thus form a veritable “miniature museum,” illustrating the values, proverbs, and founding narratives of the society. For example, a crocodile-shaped weight might evoke patience, while a seated human figure recalls the importance of wisdom and collective deliberation.

The Akan are particularly famous for these objects because their economic system was based on gold, an abundant resource in the region. The weights, kept in leather or fabric cases called dja, were much more than mere tools of commerce: they were status markers, prestige objects, and even educational materials, transmitting the philosophy and history of the people. Their use was overseen by specialists, often connected to the royal court, emphasizing their sacred and political dimension.