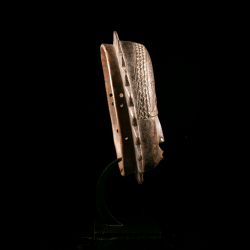

African Baule "moon" masks are rare in collections and appear only occasionally during celebrations. Contrary to the widespread belief that Baoulé tribal art is limited to facial or zoomorphic masks, this abstract circular form illustrates the Baoulé people's interest in conciseness and aesthetic purity.

Often overlooked, these masks serve as an introduction to ritual dances and demonstrate the artistic diversity of this culture.

In Baoulé tradition, Anglo-Ba masks were used to open festive ceremonies (bla able) and women's funerals (bo able), before the animal and portrait masks that closed the performance.

These celebrations, distinct from the sacred male dances, had various names depending on the region: ajusu (from Bouaké to Bocanda), gbagba (around Yamoussoukro), and ajemele (in the Béoumi region). At the beginning of these rites, the "moon" mask (sometimes accompanied by the wia, the "sun") established a link between nature and the social order, without being linked to a cult of the stars.

Baule sculptors, who tended to humanize all visible forms, often depicted a face at the center of this celestial disc. This fusion of human features and the lunar star sought to unite the distant and the near in an idealized form. The horizontal incisions at eye level allowed the wearer to perceive his surroundings, although he was also guided by his akoto (assistants).

The mask's pursed lips suggested whistling, a gesture that, according to some sculptors, expressed carelessness, reinforcing its playful role in these ceremonies.

Data sheet

You might also like

African Baule "moon" masks are rare in collections and appear only occasionally during celebrations. Contrary to the widespread belief that Baoulé tribal art is limited to facial or zoomorphic masks, this abstract circular form illustrates the Baoulé people's interest in conciseness and aesthetic purity.

Often overlooked, these masks serve as an introduction to ritual dances and demonstrate the artistic diversity of this culture.

In Baoulé tradition, Anglo-Ba masks were used to open festive ceremonies (bla able) and women's funerals (bo able), before the animal and portrait masks that closed the performance.

These celebrations, distinct from the sacred male dances, had various names depending on the region: ajusu (from Bouaké to Bocanda), gbagba (around Yamoussoukro), and ajemele (in the Béoumi region). At the beginning of these rites, the "moon" mask (sometimes accompanied by the wia, the "sun") established a link between nature and the social order, without being linked to a cult of the stars.

Baule sculptors, who tended to humanize all visible forms, often depicted a face at the center of this celestial disc. This fusion of human features and the lunar star sought to unite the distant and the near in an idealized form. The horizontal incisions at eye level allowed the wearer to perceive his surroundings, although he was also guided by his akoto (assistants).

The mask's pursed lips suggested whistling, a gesture that, according to some sculptors, expressed carelessness, reinforcing its playful role in these ceremonies.